Your donation will support the student journalists of Francis Howell Central High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs. FHCToday.com and our subsequent publications are dedicated to the students by the students. We hope you consider donating to allow us to continue our mission of a connected and well-informed student body.

Photo Illustrations by Kayla Reyes

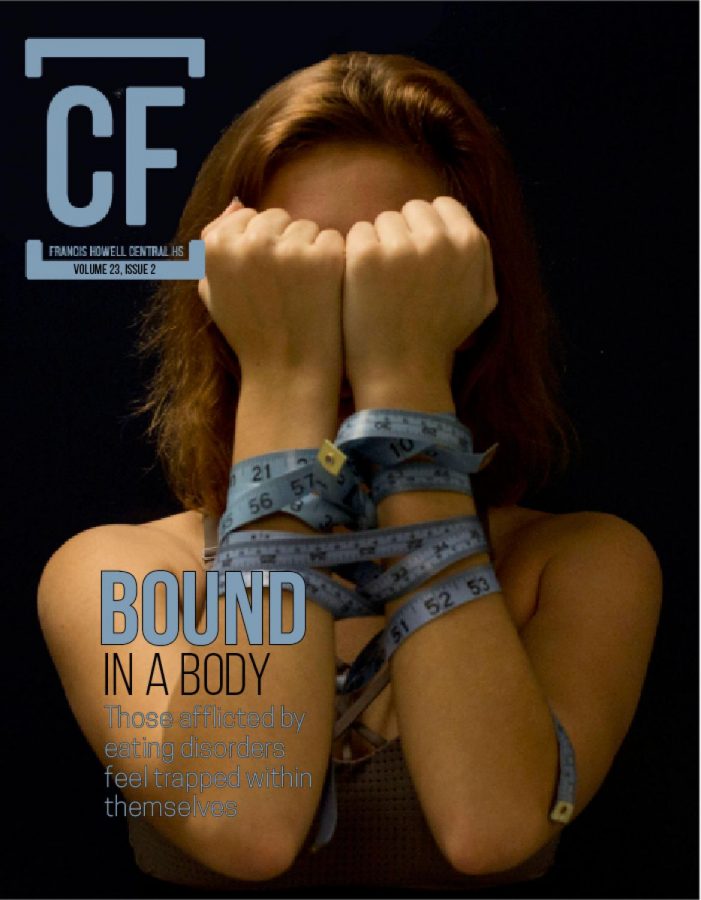

This issue, we focus on eating disorders and their negative effects in our community.

Bound In A Body

Those afflicted by eating disorders feel trapped within themselves.

November 18, 2019

Photo Illustration by Kayla Reyes

A girl looks into a mirror, measuring her waist. People affected by eating disorders often feel inadequate in their appearance and turn to unhealthy methods to become happier with themselves.

Forced To Fit (In)

The ideal body is plastered all over social media, ruining the self esteem of young individuals

She pushes through the group of students crowding the door as the bell rings. Her laces are caught under her shoes as she hurries to the cafeteria. She shuffles through the lunch line and grabs a lunch tray as quickly as possible. The vegetables on her tray remain untouched for the entire 25-minute lunch period.

In fact, she rarely glances down at the tray full of food as she makes her way into the bathroom, shoving the door open and quickly locking it. She takes a deep breath and sits on the toilet. The thought of eating makes her uncomfortable, disgusted, and weak. She sets the tray out of her way and starts working on homework instead, drowning out the sound of her stomach rumbling with the ruffling of papers. Another day goes by and not one meal has been fully digested. As she realizes lunch is about to end, she wipes her tears from her cheeks and unlocks the stall door. Her mind is flooded with negative thoughts and the flawless image of what she could be drilled in the back of her head reminds her that she never can be what everyone else is.

Almost invisible to the naked eye, eating disorders are more common than uncommon. The pressure to be perfect is advertised all over social media and in everyday society. The minds of people both young and old are tricked into thinking the ideal male body is big and bulky, or the most feminine a woman can be is with her hourglass shape and tiny figure. These images are constantly plastered into the brains of countless people, and while some can push them aside and shrug it off, others feel that this image is a must-have, and automatically feel uncomfortable and sickened with their body. So, they change what they think is the reason behind their unbearable structure; food.

Eating disorders can mean different things for different people, like any other psychological disorders, they vary from person to person, which means they see the words ‘eating disorder’ and think of divergent ideas.

Junior Kathleen Tallmadge* described eating disorders as a change in eating habits that leads to becoming a mind game that your brain controls.

“It’s an abnormal eating habit that affects the person negatively in mental and physical health,” Tallmadge said. “It’s when someone purges after they eat, or they barely eat in a day, or they eat way too much. Things like that.”

Junior Elijah Calignaoan, who has suffered with an eating disorder, defined them as something unique. “A quirk in the brain- a trick in yourself to believe what is wrong, is actually right,” Calignaoan said.

According to the National Eating Disorders Association, people that struggle with body image and a lower self-esteem tend to be more likely to develop an eating disorder.

Like someone’s definition of an eating disorder, their struggle can be different, especially how and why their eating patterns start changing. Calignaoan described how his eating habits started to slowly change.

“It just started with not eating for a day, then two and so on,” Calignaoan said. “My body just got used to not eating for a day or two at a time. It was definitely unhealthy and my friends said what I was doing was dumb and I should eat, but it wasn’t that simple. I tried eating at school and I felt lightheaded and sick. I have no idea why but I just did.”

Tallmadge also went on to explain how her habits changed and how little she would eat each day just to achieve the body society deemed as ideal.

“The [eating habits] started to form because I used to get bullied about how fat I was and how I was just bigger than everyone at school,” Tallmadge said. “And so I became extremely self-conscious. I admit that I wasn’t as skinny as others, which led to negative thoughts that started making me nauseous every time I ate food, so slowly I ate less and less to where I was eating maybe 300 [calories], sometimes less, a day.”

The average person intakes around 2000 calories per day, consuming anything lower than 1200 calories per day will send your body into ‘starvation mode’.

Although everyone’s upbringing can have different factors, they usually share one common aspect: image.

“I know it boils down to self-esteem,” Calignaoan said. “That’s the simplest way I can put it.”

According to the National Eating Disorders Association, bullying pushes the likelihood of an eating disorder forming. Bullying can lead to a decrease in self-esteem, social isolation, and poor body image, which ultimately lead to the sudden change in eating patterns.

Calignaoan also described why his habits began to change and what brought him to adapt to different eating patterns.

“As someone who has been harassed because of weight, I would do anything just to lose some more pounds just to be accepted,” Calignaoan said. “That stuck in my subconscious and I kept on continuing.”

Tallmadge elucidated that she started noticing her eating habits changing after a while. After Tallmadge noticed, her mom noticed not only how she had changed, but also the way she ate and what she ate.

“My mom noticed that there was something wrong,” Tallmadge said. “I wouldn’t eat breakfast or dinner with my family anymore because I was embarrassed.”

Calignaoan claimed that it didn’t have much of an effect on his friends or family, and that it was more personal.

“I feel accepted at home for who and what I am,” Calignaoan said. “I can eat when at home. Occasionally I’ll throw up but that doesn’t involve them. I keep to myself because I believe it would be harder to work on myself when they are constantly injecting themselves into my conflict.”

Despite knowing the consequences and effects on the body, Calignaoan claimed that he knew he had an eating disorder from the beginning, and didn’t do anything about it.

“I absolutely knew I had an eating disorder,” Calignaoan said. “I knew what I was doing from the start. I truly wish I knew why I chose to be weird and do this to myself but I did. No harm, no foul. But there was harm and I didn’t really see it at the time. Looking bad not too long ago, it’s clear as day what it did to me mentally.”

Without a doubt, having an eating disorder and the sudden change in eating habits affects your physical health and appearance, but it also affects your mental health.

“It’s definitely changed my personality,” Tallmadge said. “It seems like I’ve become a little more serious and I apologize for my actions–even if it was just talking to someone.”

As stated by the National Eating Disorders Association, having an eating disorder affects your cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and endocrine systems, as well as impacting you neurologically.

With this being said, Calignaoan went on to explain how it impacted him mentally and the lasting effect it had on him.

“It has affected me so much,” Calignaoan said. “I lost a lot of respect for myself. It only damaged my already low self-esteem and I fell into a hole that left me with scars. It was not worth it.”

Tallmadge explained the symptoms she experienced with having an irregular eating pattern.

“Headaches, stomach pains, chills, and tiredness,” Tallmadge said.

The National Eating Disorders Association listed refusal to eat certain foods, signs of uncomfort while eating around others, and skipping meals as just a few symptoms or signs of an eating disorder that is either present or forming.

With different symptoms come different coping mechanisms and adaptations, which can be very unique to the person possessing the eating disorder.

“It’s a slow process for me personally because I don’t have the kind of will power some people do,” Calignaoan said. “I just snack a lot now. I eat light stuff often so I don’t feel grossly stuffed from one sandwich.”

Tallmadge mentioned that she goes to a therapist for her eating disorder and has grown to track her calorie intake.

“I go to a therapist and I have this calories notebook,” Tallmadge said. “Whatever I eat I write it down and how many calories were in it. It’s to make sure I eat what I should to function properly and it’s there so I don’t eat less.”

According to the National Eating Disorder Association, treating an eating disorder generally involves a combination of psychological and nutritional help, along with medical and psychiatric monitoring.

“It wasn’t worth it,” Calignaoan said. “I want everyone to know it’s just not good for you and it may be affecting you more than you think. With it affecting you, it then affects people around you. Having loving friends and people who boost you up is important. Not just for eating disorders, but for life.”

*The use of asterisks next to the names of sources in this article indicate the use of a pseudonym for the protection of sour

Photo Illustrations by Kayla Reyes

A teenage girl stands hunched over a sink and looks into a mirror, her hands bound with pastel-blue tape measures. Those affected by by eating disorders often feel disgusted within their own bodies, and turn to unhealthy tactics to “fix” themselves.

The Road To Recovery

The steps in recovering from an eating disorder require intense thought and dedication

“Today I am a good weight for my height and happy in my own skin,” sophomore Emma Cowherd said in regards to her struggles with an eating disorder.

Cowherd began engaging in poor eating habits in seventh grade and went on the downhill slope towards her eating disorder.

“It started with me not feeling hungry, but then I started to see a difference and I liked how I was getting skinnier… I thought I looked better,” Cowherd said.

Cowherd, like several other high school students, notice that there is a pressure in our society to look a certain way. Skinny waist, thin legs, toned arms. Unfortunately, some of us conform to this thought process and undergo unhealthy habits to achieve an unhealthy goal.

Whether someone has struggled with an eating disorder or is struggling with an eating disorder, the most important part of it all is recovery.

Recovery is obviously not easy. According to the Eating Recovery Center, the highest risk for relapse is in the first 18 months after treatment. With relapse around the corner for some who are recovering, it takes will power and determination to stay on track to success.

According to the National Eating Disorder Organization, recovery takes five steps: pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance (or relapse).

It all begins with “pre-contemplation.” This step normally includes friends and/or family approaching someone about their eating habits. At this step, the affected individual doesn’t acknowledge the problem. Sophomore Lexi Lyons described her experience fitting this mold.

“My mom noticed and then she brought it to my attention … at first I didn’t think anything of it,” Lyons said.

For Cowherd, pre-contemplation also began with her mother.

“My mom started getting concerned when I didn’t eat dinner,” Cowherd said.

After being approached by friends and family, the “contemplation” stage sets in. Lyons began to notice what her friends and family were worried about. Recovery was beginning to be a thought worth thinking about.

“Seeing myself so small after not being that small for a really long time upset me. Really upset me. And then, I just looked at myself and I was like, ‘You’re so skinny to where its gross.’ I don’t know. It really upset me,” Lyons said.

Following these contemplative thoughts, “preparation” began. Once someone decides they need to seek help, determining how is always a difficult choice. Do they approach a parent? A friend? A counselor, or an eating disorder professional?

For most, treatment is full of unexpected barriers and obstacles. The sheer fact that these individuals will have to change a habit they have developed over time is hard as it is, but then adding on to their worries is all the questions they have. Where do I find treatment? What will treatment look like? How can I open up about my issues? All of the unexpected must be addressed first before any action can take place to ensure safety.

Once all questions are asked and answered by doctors, friends and trusted adults, “action” can finally begin.

For Lyons, action began with a doctors appointment. Being able to put a label on the habits she was forming helped her learn how to treat them.

For Cowherd, action began with her mother. Approaching someone you care about to an incomprehensible degree is understandably difficult. No one said the steps towards recovery was easy.

“Anybody who is dealing with it; It sucks. And I wish the best of luck to anybody who is dealing with the same problems,” Lyons said.

And then, we reach the hardest step; maintenance. This step is the hardest because there are so many ways in which it can go wrong.

“I am getting [to recovery] and I think I am on a track to where I wont relapse as easily,” Lyons said.

But not everyone is as lucky. For anorexia and bulimia specifically, relapse rates are between 35 and 36 percent. According to the Eating Recovery Center, relapse typically spawns from poor body image, poor social relationships, slow results from treatment, and lack of motivation to recover during and after treatment.

“The biggest challenge was convincing myself that im not getting fat. It was convincing myself that I’m getting healthy. That’s definitely the hardest part,” Lyons said.

Cowherd went through recovery and is healthier now. Cowherd was able to catch herself at an early stage, which made for a speedier recovery.

“Recovery is different for a lot of people. For me it wasn’t the hardest thing but it’s different for a lot of people and just know if you’re in the process of recovering, you can do it and believe in yourself,” Cowherd said.

The further along one is in their eating disorder, the harder recovery is; the more one has to backtrack. But along the way, there are several resources available to help.

(insert all resources)

“It doesn’t matter what other people think. Get yourself to where you’re happy and healthy,” Lyons said.

“Some advice I would give is that I know how difficult it is but you are worth more than your disorder,” Cowherd said.

Photo Illustrations by Kayla Reyes

A girl’s hands are bound in a tape measure as she covers her face. Eating disorders often make individuals feel trapped within their own bodies.

Finding Support

Reaching out to loved ones about struggles with an eating disorder is a helpful step in the process of recovery.

Like a fortune cookie, she laid: wafer thin, concealing the truth regarding the uncertain moments to come within the walls of her emaciated frame. Outside her hospital window, snow drifted down from the heavens as a chilling, serene reminder of one’s mortality. As time too drifted and she remained unconscious, her family feared the worst.

Four years ago, on Christmas Eve, sophomore Aayranna McInnis collapsed. Her heart had stopped. Born with a heart defect, McInnis was exceptionally weak because she had been starving herself for months.

“I didn’t even have the strength to look at my heart monitor,” McInnis said.

Waking from her unconscious state, she realized the path she had been walking for five months, anorexia, had waned until it was nothing more than a tightrope on which she tottered, her life and death in the balance.

“I seriously thought that was the end. I did not think I was going to make it,” McInnis recounted. “In my head, I was like, ‘Oh my God, this isn’t right. I have to fix this. I can’t, I can’t be like this.’ And I started getting really scared. And I’m like, ‘could this happen again? Could I actually die at this time?’ I don’t want to be like that, because I have so many friends here.”

McInnis’s battle with anorexia started in 6th grade.

“When I was 13, I decided it would be a good idea because I was getting bullied a lot, being called fat, chubby,” McInnis said. “So I’m like, ‘You know what? I’m going to stop eating. I’m going to do better. I’m going to make everyone else happy. I’m going to do this…Just stop eating. Stop doing what you love.’ ”

Evidently, everyone’s happiness came at a steep price, one which her body had to work overtime in order to pay.

“When I started to stop eating completely on some days, I started noticing my body started shutting down… I’m not as strong as I was before I decided to go into the starving spree that I did. Because basically when I starved myself, I didn’t think of ‘Oh, this is what’s going to cause it. I’m going to get weak. I’m getting sick.’ I wasn’t thinking that. I’m like, ‘I’m just going to get smaller and who cares?’ “ McInnis said.

Counselor Kris Miller has periodically checked in on McInnis since her freshman year to help her along the process of recovery. An experienced counselor of more than 20 years, Mr. Miller knows the detrimental impact eating disorders can have on a student.

“At its base, it’s an anxiety disorder. But, a lot of times, you know, that anxiety will increase and it can become overwhelming in terms of your ability to try to continue your regular lifestyle — keep your grades up, keep your social interactions up — because you’re so preoccupied with your eating,” said Mr. Miller.

With McInnis, as she continued to abstain from food, she likewise embarked on a social isolation binge, fasting, severing herself from family, friendship, and love — the vitamins of life.

“I didn’t want to interact with people, because I knew they could see … So I actually started withdrawing from people, including my family,” McInnis said. “When my social life went down … my mental stability went down too because without people try[ing to] talk to me, and me not letting them in, I started thinking, ‘Oh, I’m worthless. I’m not good [enough] for this.’ I started getting more angry with myself, but I started going after the people I loved [rather] than myself … [I’d] lash out at people without meaning to, but I couldn’t control myself because I was not mentally okay.”

Fortunately, McInnis’s time in the hospital proved to be a sobering turning point; she soon found strength and solace in those around her. Sophomore Dakota Dunman, a cherished confidant for McInnis since the start of her trek against the slippery slope of anorexia, has been dedicated to aiding her in her fight.

“If she needs emotional support she always calls or texts me or [she comes] to my house and just talks about life,” said Dunman.

As McInnis valiantly stands in the trenches of starvation, she does so arm in arm with Dunman and other friends, forging stronger relationships.

“We’ve bonded closer together and … we’ve had to go through a lot of challenges and tasks, especially involving her anorexia. So like, we grew really close,” said Dunman.

Similarly, McInnis’s eating disorder has reinforced her bond with her mother.

“When [my mom] saw what I had, she went, ‘You know what? Forget all those people and what they got to say. It’s just me and you — and of course your little sisters — against the world. Don’t let any man, woman, children, old people, bring you down,’” said McInnis.

McInnis’s mother has struggled with bulimia for years. Her experiences enable her to foster a new, poignant connection to her daughter.

“When my mom helps me fight this, we can better ourselves,” McInnis said. “[My mom] takes her experiences and she passes them to me and helps me through it. ‘Cause she’s like, ‘I’ve been in your shoes before… Me and you, we’re going to go at this together. Don’t think you’re by yourself.’”

Now, McInnis continues her journey with anorexia as she walks the halls of Francis Howell Central. Numbing frost may have encroached upon McInnis’s reality as she lay motionless, utterly consumed with the precious brevity of life, but through support, guidance, and persistence, the bitter cold has begun to thaw. Germinating in the grounds of gradual acceptance, her confidence is blooming, revealing that her fortune was, and is, one of inspiring hope.

Struggling Through Recovery

Lanie Sanders recounts her personal difficulties with an eating disorder

Photo Illustrations by Savannah Drnec

Lanie Sanders thrashes her head back and forth, portraying the anxiety inflicted by her eating disorder.

“Am I going to have to start weighing you again?”

My dad asked me after noticing how thin my face looked. My heart stopped. A wave of cold rushed over my body and I froze. My hands became clammy and a sinking feeling grew in my stomach. Looking down to avoid eye contact I mumbled that I was fine and prayed he would just drop it.

He didn’t.

Every week I would have to walk into my parents’ bathroom, arms wrapped around my stomach and so incredibly ashamed of myself. It was looking at my dad in the eyes as I stepped onto the scale, feeling this incredible sense of self-hatred because I knew I was letting him down. Every week I would look between my feet and feel a mixture of emotions. To some extent I was happy, seeing the number slowly trickle down. But on the other hand, I was frustrated that the number wasn’t as low as I had hoped.

It was standing in my bedroom and measuring my ‘success’ by how loose my favorite pair of jeans would be. When I noticed them getting too tight for my liking, I didn’t eat. But as my parents started to notice, it became harder and harder to hide what I was doing.

I would skip breakfast every morning because “I didn’t have time,” either throw away my lunch at school, pawn it off to a friend, or eat my only meal for the day. I would say we were getting food in one of my classes, or that I ate when I got home from school so they wouldn’t make me eat dinner. And when they did I would eat as little as possible to prevent myself from feeling the all-encompassing guilt that surrounded my consumption of food.

I tried to fix myself.

I would force myself to eat full meals because I knew how unhealthy my behavior was. But that made me sick. I tried snacking throughout the day to prevent me from feeling sick, but then I would inevitably binge on something and then fall into the same cycle of binging and purging.

For Christmas one year, I asked for Crest white strips so my teeth wouldn’t be discolored, because I was doing everything in my power to hide my behaviors from my friends and family. I started wearing oversized clothes so my dad wouldn’t notice the change in my frame.

For me it wasn’t Barbie dolls or social media, it was just a general hatred of the way I looked. It was getting my seventh-grade yearbook photo back and crying because of how fat my face looked, and then deciding that it needed to change.

For me it was asking a friend to borrow her hoodie in seventh grade gym and her saying no because “it would be way too small” for me.

I was in seventh grade, wanting to be able to wrap my hands around my thighs.

I was in seventh grade, watching YouTube videos on how to lose 10 pounds in three days.

I was in seventh grade, researching how much liposuction was and how hard I would have to work to get it as soon as I turned 18.

There was a time in freshman year where I noticed that I could see my ribs, and I remember crying tears of joy because I was finally satisfied with the way I looked.

And then one day it finally clicked for me. It was at a softball game, in near 100 degree heat. The day had been pretty long for me, I had played two games already and didn’t have much time to rest. I was standing in my position, getting ready for the pitch when I started to feel sea sick.

The world around me seemed to move in wavelike motions and I was trying my hardest to stay afloat. Overheating was nothing new to me, so I tried to take a few deep breaths and stick it out for the rest of the inning; but this time something was different.

As I called for a time-out I realized that I couldn’t hear anymore. An overwhelming ringing filled my ears as the muffled voice of the umpire called for the break. Little squares floated in my vision as I started to accept the fact that I was going to pass out. But no matter how much my body wanted to shut down, I refused to let it happen, because there was nothing I wanted less than to be that person.

So, with shaky legs and distorted vision, I walked into the dugout and sat down on the bench. They put another girl in my position and I poured my entire jug of water over my head. I knew that if I were to drink anything I would automatically throw it up, so I had to wait for the nausea to subside. I finally realized I was killing myself.

So here I am today, at 124 pounds, noticing that my favorite pair of pants are a little tight on me; but I don’t skip meals anymore, or make myself throw them up. Because even though I don’t engage in those behaviors anymore, there’s a little part of my brain that’s telling me that I’m not hungry, a little part of my brain that encourages me to stick my fingers down my throat.

On the first day of fall break I was standing in my bathroom, getting ready for work. As I was putting on my uniform I took a good look at myself and started to cry. After so long of doing well and being happy with myself, I was relapsing. With my parents out of town I knew I would be able to skip all the meals I wanted without consequence. So I did. And in a week and a half I lost 8 pounds.

I’m not better. I’m not okay. It’s like I constantly live with someone following me, waiting for me to be vulnerable and then take advantage of me. It knows when I’m weak, it knows when I’m least expecting it. Without warning I’ll once again be completely enveloped by it. Not a day goes by where I don’t partially shame myself for eating, and I really wish that wasn’t the case. For the most part I can busy myself with work or other activities to distract myself from the shame I feel, but I can never fully escape it.

Every single time I look down at my hands I’m reminded of how much I’m changing. My bones are becoming more apparent and I constantly feel the need to cup my hands together so I can feel just how thin they are and exactly what I’m doing to myself.

My eating disorder hasn’t left me and I don’t think it ever will.