Your donation will support the student journalists of Francis Howell Central High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs. FHCToday.com and our subsequent publications are dedicated to the students by the students. We hope you consider donating to allow us to continue our mission of a connected and well-informed student body.

Eyes Wide Open

Looking into others’ opinions about racial justice issues provides a new perspective from those with different experiences

November 20, 2020

Civil Rights activist Martin Luther King Jr. leads a group of protesters at a rally in the 1960’s. Like the Civil Rights movement, current protests have become a popular way to show support for racial equality

Headways Through History

The push for change by Black Lives Matter supporters parallels that of Civil Rights activists

As protestors wipe the sweat off their foreheads and tears off their cheeks, they march forward. The streets are full of people treading towards the Lincoln Memorial as the late August sun beams down on them. Protestors are carried out of the crowd because of heat exhaustion. Regardless of the discomfort and scorching heat, they march forward. 57 years later, history repeats itself. The fight for equality has been watered down since the end of the 60’s, but lately it’s been brought back to the limelight. As the Black Lives Matter movement storms media outlets and catches the eye of many all across the country, Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” slowly turns into “No Justice, No Peace” being cried all across America.

The demand for justice and equality in the U.S. is one of many examples of history repeating itself. Marches and protests for progress are nothing new in our country, with the historic March on Washington being held in August of 1963. Essentially, the Black Lives Matter movement is a prolongation of the racial injustice following the fight of the Civil Rights era. The death of George Floyd that sparked today’s protests can be compared to the death of Emmett Till, a key contributor to the start of the Civil Rights movement.

Senior Taylor Krieg participated in a BLM protest in the area and commented on the similarities between today’s marches, and those held during the Civil Rights era.

“It wasn’t until I went to a protest and saw hundreds of people march together, yelling the names of innocent people murdered simply for the color of their skin, that I noticed this nation has failed all who participated in the Civil Rights movement,” said Krieg.

Another student who engaged in a BLM protest in our area is senior Krystal Arias, who stresses the importance of protesting and how it results in slow change.

“I think the protests can do great things and hopefully will,” Arias said. “As much as I and a lot of others want things to change in the justice systems, I honestly don’t believe it will anytime soon. But, we won’t stop fighting until it does.”

Additionally, senior Gabryelle Loggins compared the struggle during the Civil Rights movement to today’s Black Lives Matter movement, and although she is unable to attend a protest, she heightened the fact that people of color are still pushing for justice.

“The only difference is the time period,” Loggins said. “We are still fighting to be equal.”

Loggins also commented on the sense of gratification she possessed after seeing people protest.

“Seeing people there made me feel unapologetically black, beautiful, and proud that my people could come together for the greater good,” Loggins said. “I think people became involved because they know for a fact there has to be change. I had no choice but to become involved because this is my reality, and this reality is going to change.”

Historically speaking, the Black Lives Matter movement and Civil Rights movement share a great amount of similarities, but they also have their differences. For example, the Civil Rights movement had its leaders who spoke out against the problems with racial injustice like Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks, John Lewis, and Robert F. Kennedy. With the Black Lives Matter movement, the key figures are people of color who have been murdered, like Michael Brown, Trayvon Martin, Elijah McCain, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd.

“Segregation might not be legal anymore,” Krieg said. “But that’s not stopping anyone from mistreating a person of color, especially the people that are supposed to protect them.”

Furthermore, Arias emphasized the impact protests have had in today’s society and how much progress we’ve made, if any.

“Things have changed, obviously,” Arias said. “But, things haven’t changed, because [black people] are still getting treated like garbage.”

With the Civil Rights movement, the goal was for people of color, specifically African Americans, to gain basic equality and not be discriminated against. The purpose of the Civil Rights movement was to end the prejudice surrounding skin color once and for all, but the fight is nowhere near a conclusion.

“The Civil Rights movement did amazing things for this country, but it didn’t finish the job,” Krieg said. “That’s what the BLM protests are, trying to finish the fight the Civil Rights movement started.”

An IPhone displays an Instagram feed from June 2, 2020– Blackout Tuesday. Supporters of the Black Lives Matter movement posted black squares to show their solidarity for Black people in a time of racial injustice.

Artificial Activism

Insincere support of a cause drowns out actual advocates’ messages

As senior Anna West scrolls through Instagram in the early afternoon of June 2, her screen is periodically flooded with a wave of darkness. Instead of a feed composed of birthday posts and selfies and photoshoots in fields of sunflowers, West’s screen is inundated by an abundance of black squares, each offering support and solidarity for Black people in the U.S. However, West is skeptical; she questions whether the people spreading awareness for the Black Lives Matter movement truly care about the cause.

Upon seeing a post from one person in particular, she is reminded of the time she sat next to him in class a few years prior. As he casually conversed with friends, a slur slipped from his mouth. The nonchalance with which West’s classmate said the N-word caused her to question his motives for posting on Blackout Tuesday. Did he truly change his racially insensitive behavior, or was his social media activism merely a result of not wanting to be labeled as racist?

Performative activism, a type of activism done to increase one’s social status rather than because of one’s dedication to an issue, stretches over many outlets for activists. It ranges from social media posts to protests and rallies. The key indicator of performative activism is one simple, yet potentially harmful trait: disingenuity.

According to Psychology and Sociology teacher Stacey Dennigmann, because the purpose of performative activism is to increase one’s social stance, it will inevitably come to an end. Once a person thinks they have posted enough, or spoken out enough, or protested enough–once they have been satisfied with the likely minimal change made, their activism will stop.

“When you’re trying to increase your social stance, it’s once you have it, once you’ve attained it: you’re no longer interested. It kind of fades out,” Mrs. Dennigmann said. “If you enter a movement because it means something to you internally, then you’re going to be committed as long as possible. When we look at motivation, internal motivation is always going to outlast external motivation.”

Mrs. Dennigmann explains that despite the temporary nature of performative activism, any attention a cause is given has the potential of being beneficial for its advancement; regardless of why people choose to partake in a movement, their participation brings awareness to it nonetheless.

“There’s always benefits of activism … What happens, kind of more so with performative activism, you see it die out more quickly,” Mrs. Dennigmann said. “But any activism can be good activism because ultimately it’s wanting change.”

Though West herself fervently supports the Black Lives Matter movement and believes there are issues with performative activism, she understands why people who may not be incredibly dedicated would speak about the movement.

“If you’re not gonna post, you’re gonna get accused of being racist… or [people] automatically assume you don’t support the movement,” West said. “[I think] there’s a lot of social pressure. If [someone] sees all these people agreeing with it, they don’t want to seem like an outcast.”

According to Mrs. Dennigmann, high levels of interaction on a social media post can lead to increased self-esteem: likes, reposts and comments can be nearly addictive. Therefore, a post about the Black Lives Matter movement, which would likely receive a high amount of engagement, would be associated with heightened levels of self-worth. For some, this may be the main motivation for making posts in support of the Black Lives Matter movement.

“When we look at social media … people, they get addicted to the likes. They get addicted to and they equate a like with a higher self-esteem,” Mrs. Dennigmann said. “When we look at people, you know, they want this sense of acceptance and belonging and they feel that’s going to fulfill them.”

Regardless of people’s motivation for spreading awareness that is not genuine, or speaking about an issue that means little to them, the downsides of doing so are clear. According to West, the insincere nature of performative activism is incredibly harmful to any cause. In regards to the Black Lives Matter movement in particular, she believes performative activism undermines the message that supporters are trying to spread.

“I think it could give [Black Lives Matter] a really bad name. If the wrong people ‘support’ something, it can be harmful if their actions don’t reflect on the actual morals of the movement,” West said.

Performative activism is a widespread issue, creeping into all corners of the movement. However, there are steps that can be taken to reduce its harmful effects. According to alumna Maddie Bennett, an avid protester and activist for the Black Lives Matter movement, the way to have the greatest impact on a cause is by letting those it affects most lead the way.

“I feel as a white person, it is important for me to support black folks in this stressful time,” Bennett said. “I am prepared to listen, walk in the back, to respect the black organizers [who put] all of their time into creating this action, and to hear black participants’ voices. I know it’s not about me.”

For those who want to avoid minimizing an issue through performative activism, West has a piece of advice.

“Educate the people around you. You don’t have to change people’s opinions, but have a voice,” West said. “Discuss it… and just try to have a voice.”

West’s biggest strategy for spreading meaningful awareness is simple; she does more than the bare minimum, and she urges others to do the same

“Posting one thing is kind of like the easiest way, and you could post that and still really care,” West said. “But try to avoid just [taking] the easy way out. Sign petitions, go to protests, just try to take an extra step.”

A black fist is held up, representing the Black Lives Matter Movement. Since its founding, the fist has been one of its symbols.

Does the Movement Matter?

A look into students’ perspectives on the Black Lives Matter movement

It is a wide-scale invasion. Materializing on plasma screens, dotting social networks, commandeering headlines of outlets everywhere. No conversation is too far away from the potential permeation of its topic. The phrase “Black Lives Matter” has taken up residence in the present conversation. It has made itself seen, regardless of whether individuals support it or not.

The phrase “Black Lives Matter” is not a new one, first used in 2013 by three Black, female organizers protesting the acquittal of George Zimmerman. In the present day, the phrase is used in much of the same way; it exhibits a concept that may be new to some: racial oppression. Rather than ignoring this concept and the three words that represent it, many younger individuals have chosen to not only confront it, but to qualify a response.

When senior Anyha’ Dorris first heard the phrase, she was confused by its simplicity.

“I mean, obviously I was like, yeah, Black lives matter, why wouldn’t [they]?…Why are we fighting over this?” Dorris said.

After doing research on her own, she was surprised at what she found: instances where Black lives weren’t treated justly.

“I was like ‘Wow, this is still happening?’” Dorris said.

For senior Tevin Tipton, the concept of racial oppression is nothing new. As a Black student, Tipton recalls several instances of biased treatment while changing schools in junior high.

“I would get asked almost every day: ‘Is my home environment stable? Do I have both parents in my house?’” Tipton explained. “Like, why do you assume these things of me just because of what I look like?”

In addition to personal experience, Tipton has observed the treatment of Black people as a whole and believes racism is still an issue in America.

“When there’s people who are mainly determined to destroy and keep another race in poverty or in stress, there only seems to be one cause of this. And it is most definitely racism,” Tipton said.

In contrast to the obvious and less obvious instances of racism, the phrase, Black Lives Matter, encourages a space for validating collective injustices and imagining an ideal future for Black Americans like Tipton.

“To me, Black Lives Matter means that one day… I’ll be able to raise my children in a world where I won’t have to worry about them being harassed or injured just from doing regular tasks, being regular people,” Tipton said.

With some individuals, the phrase “Black Lives Matter” has stirred controversy over the misconception that Black lives are more important than other lives. Senior Nick Kroll’s response to the phrase was to confirm that this is, in fact, a misconception.

“Black lives do matter…I mean all lives matter, we’re just calling attention to Black lives specifically,” Kroll explained.

Although he is in support of the racial equality that the Black Lives Matter movement stands for, his interactions with those who support the Black Lives Matter movement have done more to dishearten than to inspire him.

“To me, as an outsider, [they] seem to be, in a lot of cases, violent and a little bit intolerant,” Kroll said. “I don’t really want to associate with people who just scream and yell at people who disagree with them.”

Out of all his interactions with those in support of the movement, not all of them were peaceful.

“There are also people who have told me that I’m not really saved, I’m not a real Christian… It just kind of seems to be a little bit of a turn off [to the movement],” Kroll furthered.

When it comes to the relevance of the “Black Lives Matter” movement, Kroll bases his views largely on his everyday interactions.

“I definitely feel like [racism] was a big issue, but since [the Civil Rights Movement] I feel like it has steadily grown less,” Kroll said. “I haven’t seen any issues with race in my own experience.”

Although Kroll doesn’t address racism as a pressing issue, he fully supports those in favor of exercising their right to assemble on the matter.

“I may not stand with you on what you’re protesting, but I will not stop you from protesting,” Kroll stated.

Many protesters are pushing for police reform as a result of an accumulation of videos and accounts–both new and old–portraying people of color being mistreated by law enforcement.

Tipton’s response to the influx of instances of racial discrimination within the justice system is one of relief. Though the evidence is less than satisfactory, the acknowledgement that accompanies it is a step in the right direction.

“Finally, there’s a lot more people putting out information about what’s really happening every day that usually no one would know about,” Tipton said. “Just for a minor traffic violation, [I] shouldn’t have to feel like I could lose my life.”

The threat felt by Tipton and other Black people is one that, a majority would agree, should not exist, but does.

Having attended many protests with goals to abolish the need to fear police, Dorris agrees that there is much change to be made.

“[On ‘Live PD’], I’ve never seen a negative interaction where I’ve been like, ‘Oh, that’s not okay, why are they doing that to another person?…But with the George Floyd thing, and Breonna Taylor, [and] Elijah McClain…and hundreds of more cases just like them, those police officers and more should 100 percent get more training on how to handle situations like that,” Dorris explained.

Dorris’s indigence is a shared one. Many individuals see the casualties of Black people at the hands of police as a cause worth implementing change over. A popular response to these instances is that the government should “defund the police”–the reallocation of funds from the police department to other forms of non-violent public safety.

When faced with these ideas, Kroll’s first response was to uphold the efforts and bravery of those enforcing the law.

“I don’t think it’s necessary [to defund the police]. I think [the police] are doing a good job given all the stress and danger that they’re putting themselves in every day… choosing to serve our country in that way is honorable,” Kroll said.

However, he agreed that some form of alternative law enforcement could be helpful in reducing casualties inflicted by police.

“Maybe it would be a good idea to have some instances where if you would normally call the police, you would have someone else go… Instead of sending a police officer, you send a social worker,” Kroll explained.

Individuals concerning themselves with the Black Lives Matter conversation have a wide plethora of propositions for what to change and how to implement those changes.

Luckily, access to information on these topics isn’t exclusive: it’s on social media, news outlets, cable. Topics like Black Lives Matter permeate our culture. Age aside, anyone who cares about the current conversation can enter it; nobody is too young to be passionate about issues happening in their world.

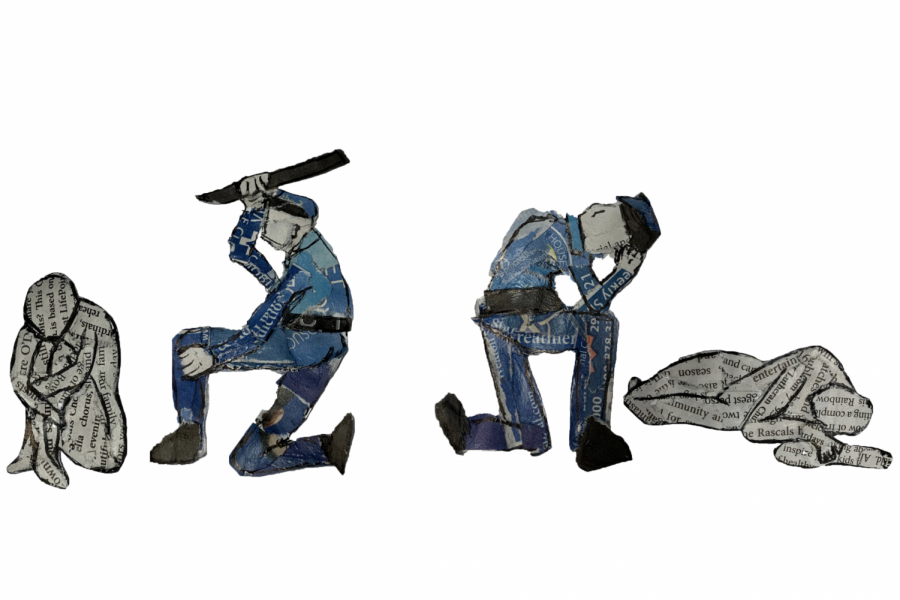

Good Cop, Bad Cop

Are individual officers at fault for police brutality, or is the system responsible?

A police officer kneels with an injured individual; another raises a baton, striking a person who cradles out of fear. The figures are made of newspaper, demonstrating that, regardless of whether explicitly stated, much of the media has taken a stance on the topic of police brutality.

Unfortunately, not everything is black and white. The yins and yangs of our universe aren’t separated with clear lines. The morality of our actions is, and forever will be, ambiguous. Trying to separate the good from the evil is not an easy task and should not be taken lightly.

The growing concern for the ethics of this country’s police system is no exception to the ambiguity within the roots of society. Drawing the lines between what an officer can and cannot do with a moral compass varies from person to person. Yet while politicians and activists debate on where these lines are, citizens are being killed.

Terrance Thompson, a security officer at Francis Howell Central with more than 20 years under his belt often works and is associated with police and law enforcement. He sees and acknowledges the good officers do for Saint Charles County, but also sees the flaws in police departments across the country.

“When I was 13 years old I was walking to the laundromat and I just happened to run into a police officer that was patrolling the area. For no reason, whatsoever, he decided that – I was carrying loads of clothes in my hands – for no reason, he decided to walk up behind me and ask a bunch of questions. I went to ignore him and he slapped my stuff out of my hands and pushed me and asked me questions and I’m like, ‘Why are you doing this? Why are you touching me? Why are you bothering me? I’ve done nothing wrong.’”

“I mean it’s just certain experiences I’ve had to let me know there is a better way to do the job,” said Officer Thompson.

Police brutality has been a recurring theme in the media for the past several months. It is undeniable that police brutality is present in our society, but there is plenty of debate over where the problem is, and who exactly is at fault. Blame has been put on the affected individuals for not cooperating with law enforcement, officers for being racist or abusive of their position, and the police system as a whole for leading law enforcement with more power than justly deserved.

When asked about where the problem of police brutality arises, Officer Thompson is inclined to believe a disproportion of power might be the source.

“There has to come a point where you as a police officer [realize that] you’re not the judge, you’re not the jury, and you’re not the executioner,” Officer Thompson said. “If it’s possible to apprehend and arrest this person, do that. Don’t take it upon yourself to decide whether or not they live or die. That’s not your job.”

Sophomore Emma Willis’s father works for the Bellefontaine Neighbors Police Department as a Lieutenant and was formerly a firearms instructor and a baton instructor, according to Bellefontaine Neighbors Police Department’s Facebook page. After discussing with her father, Willis crafted her own ideas on where police brutality begins.

“The police training program has many flaws,” Willis said. “I know many people that have gone through the academy and as soon as they are put in the field they quit. They aren’t prepared enough for all the stress and fear they’re about to endure.”

The issue of police training not being satisfactory for serving the public has been brought up time and time again. According to the University of Missouri Extension Law Enforcement Training Institution, “[officers] receive almost 700 hours of training that exceeds Missouri’s minimum requirements for peace officer certification.”

Although exceeding the minimum may sound positive, the 700 hours received still isn’t much in comparison to other occupations. For example, in Missouri, the requirement for a barbers license is 1000 hours minimum (according to a Beauty License Directory).

Senior Carson Howe’s father has been an officer for the Saint Charles County police department for over 20 years. Howe remarks that he and his father have very different opinions on the topic of police brutality. Howe also believes, like Willis, that the training officers receive may need change.

“Our training systems vary wildly from state to state, even county to county, causing no real generalized training for officers, meaning one county could be having officers trained to kill while another [trains] officers to use deadly force as a final option,” Howe said.

Current media has been persistent in blaming individual officers and the police system in its entirety. Howe sees both sides to these claims.

“I believe the individual officer[s] should be held accountable for their own actions and those actions should not be reflected on the entire system and police everywhere,” Howe said. “I do, however, believe there are issues with the system, in that there are very few ways to enforce proper transparency with the public.”

On the other side of the same token, Willis acknowledges there are several individual officers who do benefit the community and represent the system with honor.

“The officers I know went into that line of work to help people in the communities,” Willis said.

Her father, who used to face crime on a day-to-day basis, was promoted to Lieutenant and no longer interacts directly with those who need officers.

“[My father] told me it’s upsetting because he misses the feeling of being able to change someone’s life the best they can with each call,” Willis said.

Because some officers do wish to change lives, phrases like ACAB (all cops are bastards) might invalidate the risks they take to protect others. ACAB attacks not only the individual officers but also the law enforcement system in its entirety. Howe feels, similarly to Willis, that these remarks should not be taken lightly and may be out of place.

“Consider these officers as human beings too, they have to deal with some of the darkest parts of the human psyche, and many times watch as officers around them begin acting as thugs, threatening and wielding power over those they’re supposed to protect. So in short, [ACAB supporters] have become so ignorant to the point they cannot see the individual behind the uniform,” Howe said.

Despite the individuals Howe references, and even Lieutenant Willis who represents the good in the police system, Officer Thompson believes there are other officers who have a poor mentality about their job.

“I believe for certain aspects of police, it’s a superiority complex. [Officers think] ‘I’m a police officer, I can basically do what I want. I don’t have to justify it, I don’t have to give a cause for it’,” Officer Thompson said. “I’m willing to support any police officer… but there has to be accountability somewhere.”

Regardless of where the problem of police brutality stems from, there is also debate over a possible solution. The media has pitched the suggestion of defunding the police entirely. Some have suggested different methods of training, stronger background checks, and routine psych tests. Others call for change with how we interact with officers to improve the culture of citizen/police interactions.

Officer Thompson urges the necessity for a police department despite police defunding activists.

“When you’re talking about defunding the police, [think about] if you were to take the police away, there would be anarchy in this country. So we need the police, but we just need a different mindset in that uniform. And that goes about doing background checks and different [requirements],” Officer Thompson said.

Through thick and thin, officers see crime, theft, abuse, and other misdemeanors on the daily. As a society, making sure these officers are held to the highest standards is important, as is making sure these officers are treated respectfully and reciprocate that respectsw to citizens around them.

“Not everyone can be a police officer just like not everyone can be a school teacher. Not everyone is meant to be a fireman or a space cadet for that matter. Not everyone is meant to do a certain job,” Officer Thompson said. “But you have to pick the person who has the personality to do it.”