For two weeks in April, the usual rhythm of the school day at Francis Howell Central came to a halt. The school implemented a block schedule to accommodate End-of-Course (EOC) exams, replacing the traditional seven-period format with four longer, 90-minute classes on alternating days.

While temporary, the shift disrupted routines, reshaped class time, and sparked debate among students and teachers about how school should be structured, not just during testing but all year round.

The goal, according to administrators, was to reduce daily disruptions and give students the time they needed to focus during state testing. But as the schedule change unfolded, students and staff alike wondered whether the shift offered a glimpse into the future or just two slow-moving weeks best left behind. While some students praised the change, others said the longer classes made the day feel sluggish and unproductive, especially in classes where there was no testing.

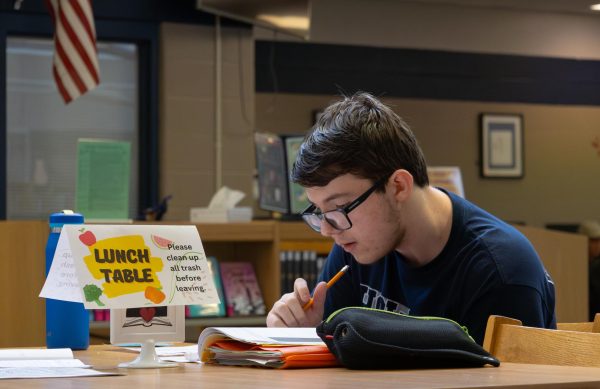

Unlike others, junior Luke Stallings welcomed the shift.

“It’s like a regular school day, but you have more time for your hour, and it’s split in half… it gives you more time to get help with problems, and it feels easier with the amount of homework you have to do each night,” he said.

Stallings’ support for block scheduling was rooted in time management. With fewer classes per day and longer periods to complete assignments, he said he had “a lot less work each night” and was able to stay focused during longer instructional blocks.

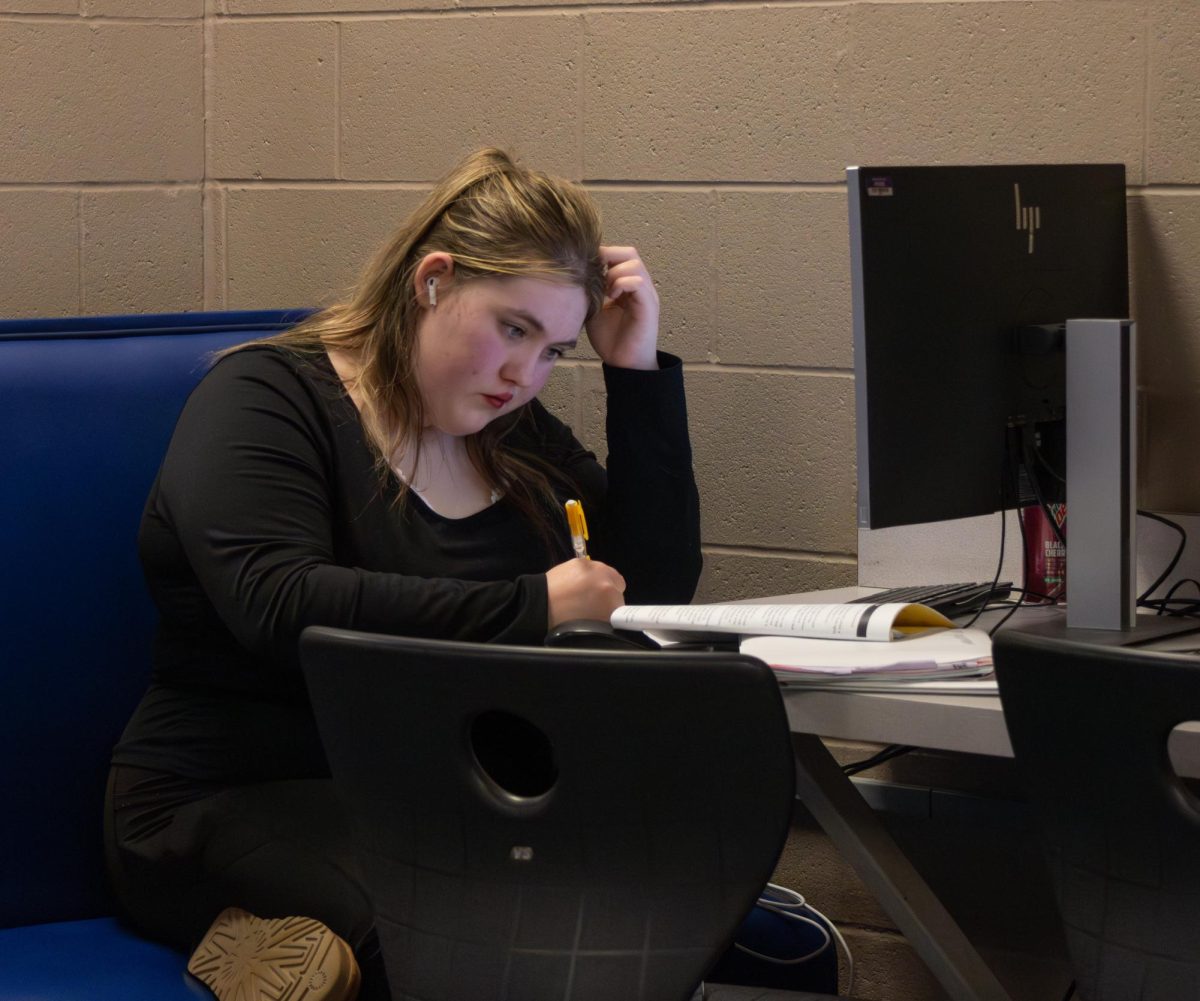

But not all students saw it in the same way. Sophomore Gabby Bess found the slower-paced days draining.

“I think it just makes the day go by way slower…I [was] bored because we’d be in one place for so long,” Bess said.

While she acknowledged that block scheduling may offer more one-on-one time with teachers, Bess believed it more often led to wasted time, especially on non-testing days when instructions were unclear.

“I think that block scheduling is a big waste of time on days that we don’t even have EOCs, because usually the teachers think we’re doing stuff in our EOC class [and] they don’t give us work, so we just sit there and do nothing,” she said.

Among faculty, the sentiment was more measured. Science teacher Patrick Reed recognized that the effectiveness of block periods varied greatly by subject. In some classes, the longer format made sense, while in others, it didn’t.

“Obviously, the time is much longer, which can be beneficial in some classes, like in science, if we need to do a lab, we don’t have to rush,” Reed said.

But in others, especially content-heavy or lecture-based courses, the long period could be counterproductive.

“ You don’t need 90 minutes of math. You need time and then practice, and then time and then practice,” Reed said. “If not planned properly by teachers, it can be really, probably a negative experience for students, because it results in a lot more downtime or wasted time.”

Reed emphasized that the schedule itself isn’t inherently good or bad. What matters is whether teachers are prepared to use their time effectively. To make the most of it, Reed said he adapted his class plan during the block weeks.

“I try to be conscientious in making sure that I don’t waste time, but at the same time, I don’t like to destroy kids’ brains with the same thing for 90 minutes,” Reed said.

Looking beyond EOC testing, the question remains whether a permanent switch to block scheduling could ever be feasible. Some, like Stallings, believe it’s a possibility. Bess disagreed.

“No, because we’ve had the schedule the way it is for so long. I don’t think it’s ever gonna change,” she said.

Reed was skeptical as well.

“I doubt it. If it happened, I would be fine with it. I just don’t think there’s an appetite for it,” Reed said.

He added that he once proposed a compromise schedule to the district.

“Monday would have been a normal day, Tuesday and Wednesday would have been block days… Thursday and Friday would have been two more normal days,” he said.

Though his proposal received support locally, it never materialized.

“Our building was pretty good with the idea, but the district said that all three buildings had to agree, and the other two schools did not want to do it,” he said.

Whether or not the school adopts block scheduling again, the trial revealed something important: students are not a monolith, and one schedule does not fit all. Some students thrive with fewer transitions and more time in class. Others feel lost in the long stretches of idle time. For now, the regular bell schedule has returned, and with it, the familiar rhythm of short periods, crowded hallways, and quick transitions. But whether the clock ticks in 52-minute bursts or 90-minute marathons, what students seem to want most is a school structure that respects their time — and uses it wisely.