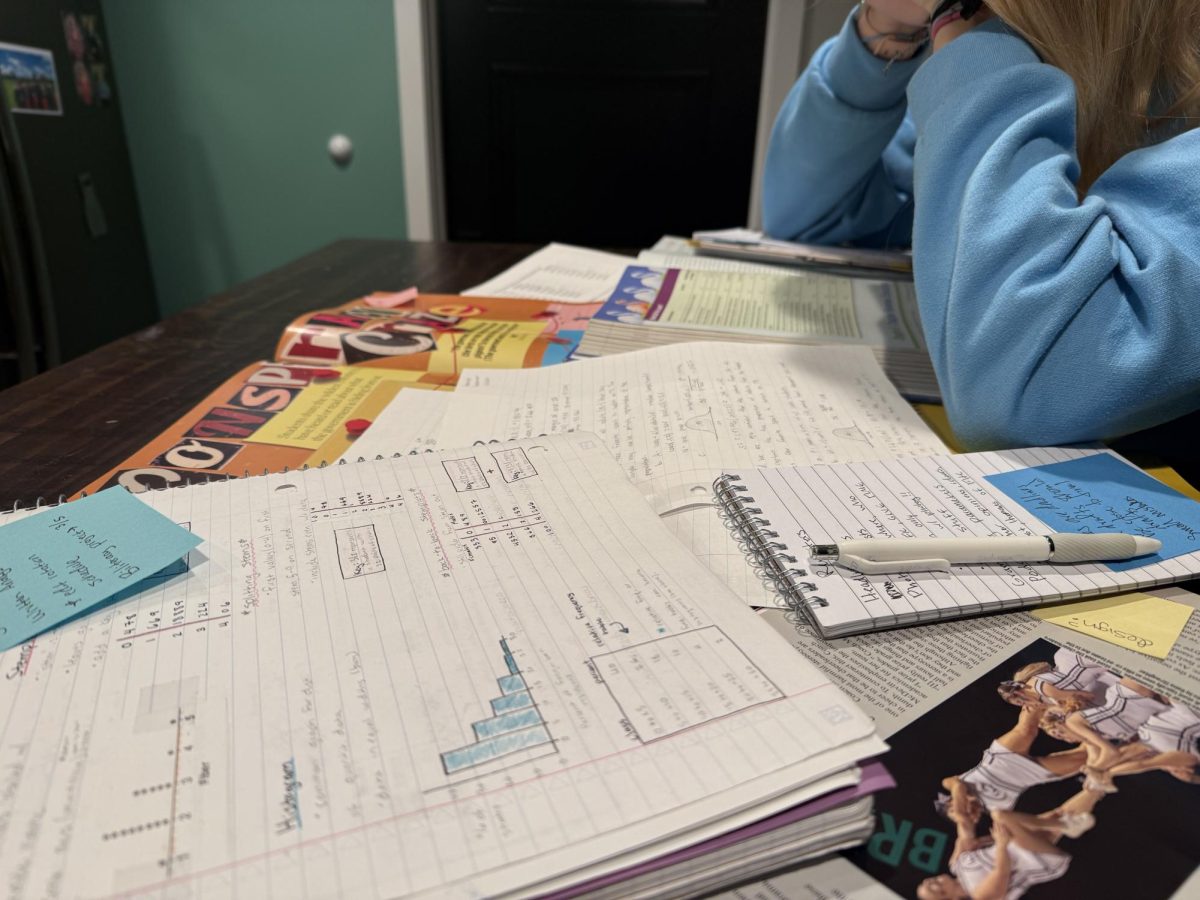

My hair is tied up in a messy ponytail, I’m wearing my favorite sweatshirt, I have an iced coffee to my left and my notebook detailing a story outline to my right. Everything is ready for me to sit down and write — but my fingers freeze over the keys, paralyzed by a sudden fear. My mind flashes back to the last article I wrote. That one was good. This one will almost certainly not be as good. Everyone will know I’ve fallen off, just another one of those “she peaked in high school” types. Eighteen and already washed up, who would’ve thought? I shut my computer, grab my coffee, and start a new episode of “Gilmore Girls,” where every episode has a neatly contained conflict and solution. Forty-two minutes of original, funny, tightly-written dialogue and plot. I will never be this good. Every book on my shelf is by an author who is more successful than I could ever be. Why try when I am destined to fall short?

This inability to begin because of my fear of the end result is not confined to writing. I’ve started to feel it everywhere. Once I was turned down for the final interview round of a competitive scholarship, I started to question my writing and strength in interviews. The rejection stung. After picking up three fouls and missing two easy shots in the first minutes of a basketball game, I was far too content to sit on the bench, watching from the sidelines where I couldn’t make any more mistakes. I couldn’t say exactly when it happened, but at some point, I had started to dread failing more than I liked to succeed.

Half of my problem is how I define success. Have I succeeded if I haven’t done every single thing as perfectly as possible? Of course not. That would mean settling for less. I set high standards because I believe I can achieve them — or at least, I used to believe that. Doubting my ability to meet demands of my own design has been a frequent occurrence in recent months. Since I’m unable to begin anything I could possibly fail, my to-do lists are never-ending — perfectionism and procrastination are a deadly combination.

So there’s the problem. To see it doesn’t require Holmesian skill; the mystery of solving it seems to. After a couple days of moping around and glancing at my monstrous to-do list, hoping it might disappear on its own, I finally stumbled on a quasi-solution. Every item or goal on the list could be separated into one of two categories. There are things I can 100% succeed in, just through some effort. Then, there are things I can 100% compete for. Finishing my English assignment? Something I can succeed in. Getting the 4x800m relay to state this year? Something I can compete for.

The “compete for” list is scarier in some ways — it represents all the ways I could fail to reach my goals. I could fall short, even when I’ve put everything I have into it. However, there is reassurance in both lists too, because I can succeed in one list, and I can take some risks in the other. I need a mixture of things I know I can do and things I can try to do. No risk-taking means no failure, but it also comes with a lot of regret. I would rather fail while trying than fail because I never tried.

As I write this, I sit criss-cross in my bed, hunched over a borrowed laptop. It’s not the perfect setup. And this isn’t the perfect story, or exactly the one I had in mind when I sat down to write it. I could sit with my notebook and coffee and write nothing, perfectly. Or I can sit in my haphazardly-made bed, surrounded by the laundry I need to fold, and write something, meaningfully. I might as well try.