There’s Nothing Wrong with Diversity

The reality of critical race theory’s relation to the new Black history and literature courses

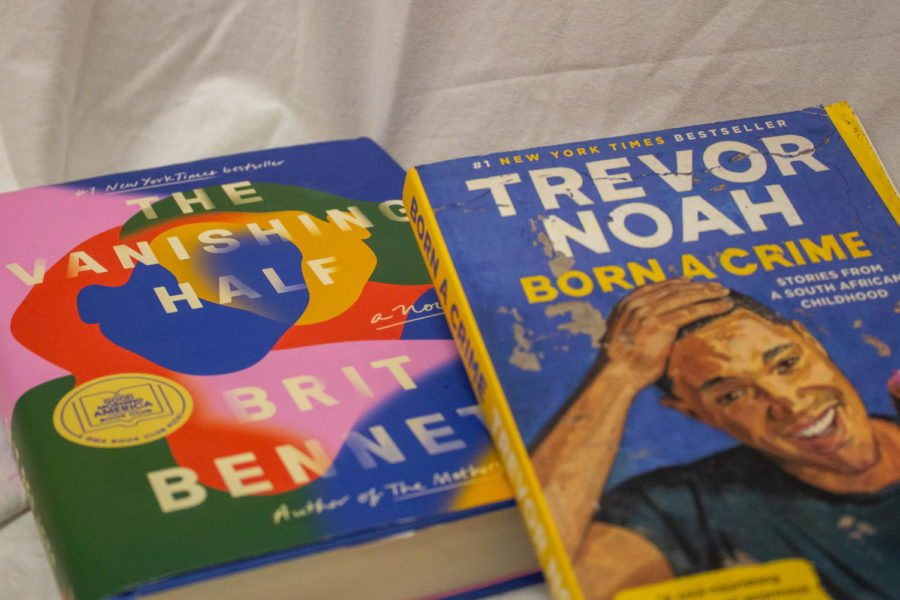

The novels, “The Vanishing Half” by Brit Bennett and “Born a Crime” by Trevor Noah, are pictured. These novels are just two examples of what students will read in the new Black literature course at FHC. The course is aimed at promoting diversity and allowing students to learn about the Black community’s influence in American society. However, this course has remained at the center of controversy in the community since its introduction.

It was the evening of July 15. Inside Westwood Trail Academy, dozens of angry parents filed into a room set-up to house the Francis Howell School District’s monthly Board of Education meeting. Some were preparing to speak to the Board. Some were holding signs. All were patiently awaiting the discussion of one matter on the agenda for the night: curriculum approval and reading for the new Black history and Black literature elective courses to be offered at the high schools the upcoming school year.

Not everyone in the room was angry though. As a student of color, senior Alexis Barnes was ecstatic to finally see her cultural heritage represented among the dozens of other history and English courses offered in the district. To her, it was a chance for her and others to finally learn about another ethnic background and understand more about the true history of the United States of America. It was a hope that maybe these classes would open up some level of understanding about different backgrounds within the student body. But Barnes’ excitement soon faded as she saw the raging faces of the parents who had come to speak at the meeting. Suddenly, she was met face-to-face with people who wanted to deny her greatest wish for more inclusion and diversity at her school.

“The adults in the community that I live in, the adults who pay their taxes to help our school so I can get a quality education, would be trying to take away an opportunity for students to learn about Black heritage,” Barnes said. “It hurts. As a student of color, in a PWI (predominantly white institution) I deserve to learn about black history. The same as a white student is able to learn about European history.”

Later, she learned that the parents had come to the meeting under the notion made by a Facebook post that there were to be three classes – one of which entirely dedicated to making white students feel ashamed of their history.

What the parents at the meeting had in mind was that the new courses to be offered by FHSD were just critical race theory hidden in plain sight. However, both their accusation toward the courses and their definition of critical race theory are blatantly false. According to an article by Education Week, critical race theory is an academic idea of thought which states that race is simply a social construct and that racism solely exists because it has been infused into our country’s legal systems and policies since its founding. There is nothing in the definition of critical race theory which says that it is meant to make white people feel bad about their history.

This goes against the narratives that many conservative politicians and television personalities have told their audiences about critical race theory. Instead, they tell their audiences that the theory exists as a way to suppress white children into believing they are horrible people and need to apologize to their Black classmates. What this fear-filled idea stems from is the realization that our country’s history is flawed, but that’s just like any other country. America has never been perfect, despite what many would wish to believe. There has been racism rooted in our government institutions since the 1787 Constitutional Convention agreed to the Three-fifths Compromise.

The new high school elective courses are not critical race theory in the slightest. In fact, there is no possible way they could be critical race theory because they are not college-level courses. Critical race theory is a concept that was created and designed to be taught in college classrooms, not a high school classroom.

In a survey done by the Missouri Department of Elementary and Secondary Education, the only school district in the state of Missouri who stated that they did teach critical race theory was Kansas City Public Schools. In the explanation section, the school district explained that “[They] offer an African centered college prep magnet school that services both elementary and secondary students.”

Other school districts did say their board-approved curriculum included the New York Times’ 1619 Project – a journalism project developed by Nikole Hannah-Jones and fellow New York Times writers discussing the legacy of slavery and the achievements of Black Americans in the national narrative – but only as a small part of a unit in a few grades or as a potential resource for teachers. In the same survey, FHSD responded “no” to having either critical race theory or the 1619 Project as part of its curriculum.

What are the new courses then? To put it simply, they are just courses showcasing Black literature and Black history and are meant to be nothing more than that. These courses were created because in the regular curriculum, a lot of events and stories pertaining to Black heritage are not covered for the sake of time. The majority of students will never hear anything about the Tulsa Race Massacre or read the novel “Born a Crime” by Trevor Noah in their current history and English courses. In fact, the majority of people who have learned and researched about these topics have done so using various videos, articles or books bought themselves, not from a school textbook. However, not many students would take the time out of their day to research a historical event or read a book about one man’s experience growing up in South Africa, unless it has some sort of connection to them personally. This puts the majority of students at a disadvantage because not only are they missing out on a quality education that covers all various topics, but they miss learning about a heritage and experiences that may be different from their own, even though these experiences are still the stories of fellow Americans.

“Our society has changed and it’s more important now than ever to allow all students, no matter their race, to invest and learn about a history that may not be ‘their own’,” Barnes stated. “Black history is American history. And Black literature is American literature.”

Learning about other cultures and perspectives is important to developing understanding and empathy for other people. This is vital for all people, but especially for children because their minds and views of the world are still forming and developing. When this opportunity is taken away from students, especially those who live sheltered lives in predominantly white areas, they may not get another chance to learn about what people of other races and cultures have or do experience.

The main importance of the courses, however, is so Black students can learn about their origins. For a lot of people, learning about their cultural heritage and where they came from is a deeply personal topic that is imperative to their identity. Dismissing students’ abilities to learn about their heritage in school says to them that their culture is not important and neither is their individual identity, that they are just part of the crowd. Barnes even mentioned that most information provided to Black students about their history is highly outdated.

“These [courses] are important because [they] offer a more in-depth experience about Black History, and how it has helped further our society,” Barnes explained. “This allows Black students to learn more about their culture and heritage, that isn’t from the textbook that was written 20 years ago.”

In a community that is supposed to be driven by love, Barnes feels hurt by the public’s responses to the new courses.

“The backlash for the class hurt me in a different way. Our community is supposed to be a model for diversity and inclusivity,” Barnes said. “So why should two classes, about the second largest ethnic group in FHC and FHSD, tear apart our community?”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Francis Howell Central High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs. FHCToday.com and our subsequent publications are dedicated to the students by the students. We hope you consider donating to allow us to continue our mission of a connected and well-informed student body.