Truth Be Told

Students from diverse backgrounds detail the challenges they have faced and how they have learned to overcome them

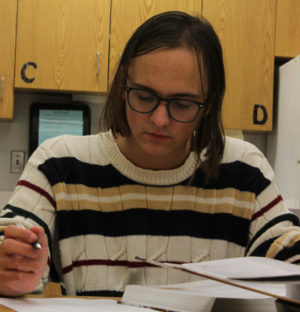

Working in class among her peers on a whiteboard, sophomore Jessica Ayres has experienced backlash at school from her choice to veil, but she finds sanctuary in veiling. “I find it very liberating actually, [veiling] makes me feel better about myself,” Ayres said.

Imagine every human as a snowflake and every snowflake is unique. They are made from the same material, yet each have their own prisms, facets, and branches, determining what they look like, how and when they fall, and where they land. The wind, a system of prejudice categorization, divides all snowflakes into common labels. The powerful gusts of wind act as a limiting factor for those snowflakes which cannot fit inside these predisposed categories. Thus, these individuals end up isolated amongst the whirlwind of other snowflakes.

Education systems are a primary example of this phenomenon. Many culturally diverse students are excluded from the accepted mainstream ideas people carry, leaving these students abandoned at an institution that is meant to socialize, include, and teach them. But, how can they learn when they are isolated?

Per the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) in 2021, “The diversity score of Francis Howell Central High School is 0.32, which is less than the diversity score at a state average of 0.49. The school’s diversity has stayed relatively flat over five school years.” With a school community where their diversity score is below average, students of differing identities are likely to struggle fitting in and finding acceptance, and are most often subject to discrimination, and evidently become isolated from the majority.

The isolation they have felt has forced them to come to affirm aspects of their identity as their authentic selves, alone. Namely, sexual orientation plays into a student’s everyday life. Despite its primarily private aspects in a teens life, sexual orientation is commonly expressed publicly. Senior Nate David, who identifies as a gay man has found struggles between expressing his identity openly and the way students around him receive it.

“I feel like if I came in the outfits that I would actually want to wear and want to be different [in]…I’d get judged,” David said.

David, navigating his way through this adversity has learned how challenging it is to be his genuine self in an environment where he feels like an outlier. Moreover, David has faced prejudice in his own learning environment, by the actions of others that choose to avoid him, or avoid his presence altogether.

“If I don’t align with the same people or same beliefs, they don’t like me on a personal level,” David said.

While this rejection is difficult to handle initially, David has come to understand that if the students around him choose to discriminate against him based on his sexuality, there’s no need for concern for their acceptance. Similarly, senior Chinecherum (Cherie) Okechukwu, a black student from Nigeria, has faced animosity from others due to the way that she and others choose to wear their hair.

“A lot of black people do not like having [their] natural hair out. It’s just looked down upon, and I think that it shouldn’t; [white people have their] natural hair out. We should be able to love our hair and that’s what I do. I either have braids or an afro and I think that is a big part of my race and my culture,” Okechukwu said.

Ridiculing a student on the way they choose to express themselves by means of a hairstyle is trivial. Being an outlier to the perceived norm, Okechukwu mentioned she would be willing to go as far as to forgo her cultural identity to end the insults.

“A lot of people talk about my accent. Some people say it’s difficult for them to understand what I’m saying [and] some people say it’s beautiful. Just a lot of comments about my accent and sometimes I wish I [didn’t] have an accent.”

Furthermore, NCES cites Central as having “minority enrollment [as] 18% of the student body (majority Black and Hispanic), which is lower than the Missouri state average of 30% (majority Black)” (2021). Still, Central is below the median for the state, thus failing to encourage inclusivity of diverse races and culture. Despite facing harsh treatment of her race and ethnicity, Okechkwu has learned that others’ opinions don’t determine her pride in her nationality.

“I’m proud of being a Nigerian and any questions people ask, I’m gonna bring it out more. I want to be able to let people know [who] I am,” Okechukwu said.

When culturally diverse students are given the space to educate others about their race, ethnicity, and nationality, the boundaries dividing them fade away, and new opportunities to discuss other aspects of identity arise. Junior Rabeea Bari follows the Islamic faith and chooses to veil, meaning she covers her head and neck with a scarf, as a way for women to be protected in every way.

“It’s not just physical. It’s also spiritual, emotional, so it means watching how you talk and watching how you behave,” Bari said. “I’m in control of my body. You don’t get to sexualize me, you don’t get to look at me. I only show you what I choose to show you.”

Veiling is mindful and intentional to women following the Islamic faith, but unfortunately, uneducated students associate it with negative beliefs and misconceptions about a peaceful religion. Sophomore Jessica Ayres is another Muslim student who chooses to veil and she has sadly faced bigotry while trying to receive an education.

“People [go] around taking pictures of me and [post] them on Snapchat,” Ayres said. “I’ve had a lot of people yell things at me in the hallway. Like, you know, one of them said ‘She’s a terrorist, she has a bomb in her backpack.’ There are just people who don’t understand, it’s just society. I’ve had kids yell ‘Allahu Akbar’ at me in the hallway.”

In light of the hostility received, Ayers sees her veiling as liberating, in that it makes her feel better about herself by giving her the confidence to express her faith.

“It means a lot to me because I like [to be obedient] to my faith, so for me to not be able to do that would make me very unhappy. I’m happy that I’m able to [veil], that I’m able to wear [my veil] and express myself the way I do,” Ayers said.

With the multitude of different cultures present at Central, but also an overwhelming opposing amount of identical racial and ethnic people, there arises a need for diverse cultures to bond together. MAC Scholars, the Multicultural Achievement Committee, fills that need as diverse students can collaborate together over common experiences with a shared perspective. Sponsor Mr. Devon Thomas, oversees the club and upholds its purpose.

“To allow the minorities in the school, the cultures who are underrepresented, a more equitable program to make sure that everybody has a place that not only they can call home, [but] that they can feel valued, supported, and have the resources that they need,” Thomas said.

Given the experiences diverse students at Central have gone through, MAC Scholars is necessary to connect students with unique identities together. As students with varied identities come together, they can begin to expand their cultures outwardly, enlightening uneducated students around them.

“I think Central and America as a whole [are] like mixing pot[s]. So I think when we take our own cultural values that came from our home countr[ies], and we put those into Central we diversify the space and we bring attention to things that aren’t always paid attention to,” Bari said.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Francis Howell Central High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs. FHCToday.com and our subsequent publications are dedicated to the students by the students. We hope you consider donating to allow us to continue our mission of a connected and well-informed student body.

![Working in class among her peers on a whiteboard, sophomore Jessica Ayres has experienced backlash at school from her choice to veil, but she finds sanctuary in veiling. "I find it very liberating actually, [veiling] makes me feel better about myself," Ayres said.](https://fhctoday.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/IMG_9229-900x600.jpg)