Between my last year in middle school and my first in high school, I went through the worst years of my life. Sizeable contributors were mental health issues like severe depression and social anxiety, but it took a major turn for the worse when I chanced upon a certain community on social media.

There were people openly discussing their eating disorders and self-harm addictions, and tutorial threads on how to get worse. How to limit hunger cravings, workouts that efficiently burn calories, tools most efficient for self-harm, small-calorie foods, it went on and on. It scared me, but I felt a little less alone in my insecurities. So I kept on watching from afar.

To an eighth grader who’d been watching “Super Size Me,” a documentary about obesity, every year of middle school, a space where people enabled eating disorders and self-harm had an impact on me. I had already been skipping meals to try and feel like I was in control of something, but I started looking at my body, too.

And I’ve been reeling from that impact ever since.

It’s not exactly what I made it sound like — a majority of the online community I speak of isn’t there to motivate others to starve to death or slit their wrists. It’s not uncommon for people to feel less alone in their struggles like I did if they find someone else going through the same thing. In fact, that’s one of the many reasons why group therapy exists, and why it helps a lot of people. But this abstract and unmoderated online form of group therapy made me feel horrible.

However, it can be hard to filter online discussion on such a large platform. There were accounts with thousands of posts and followers, even more accounts with barely any at all, and most of them found creative ways to bypass getting banned. I’ve gone to group therapy many times, and it was infinitely more helpful for my mental health than shadowing those online discussions.

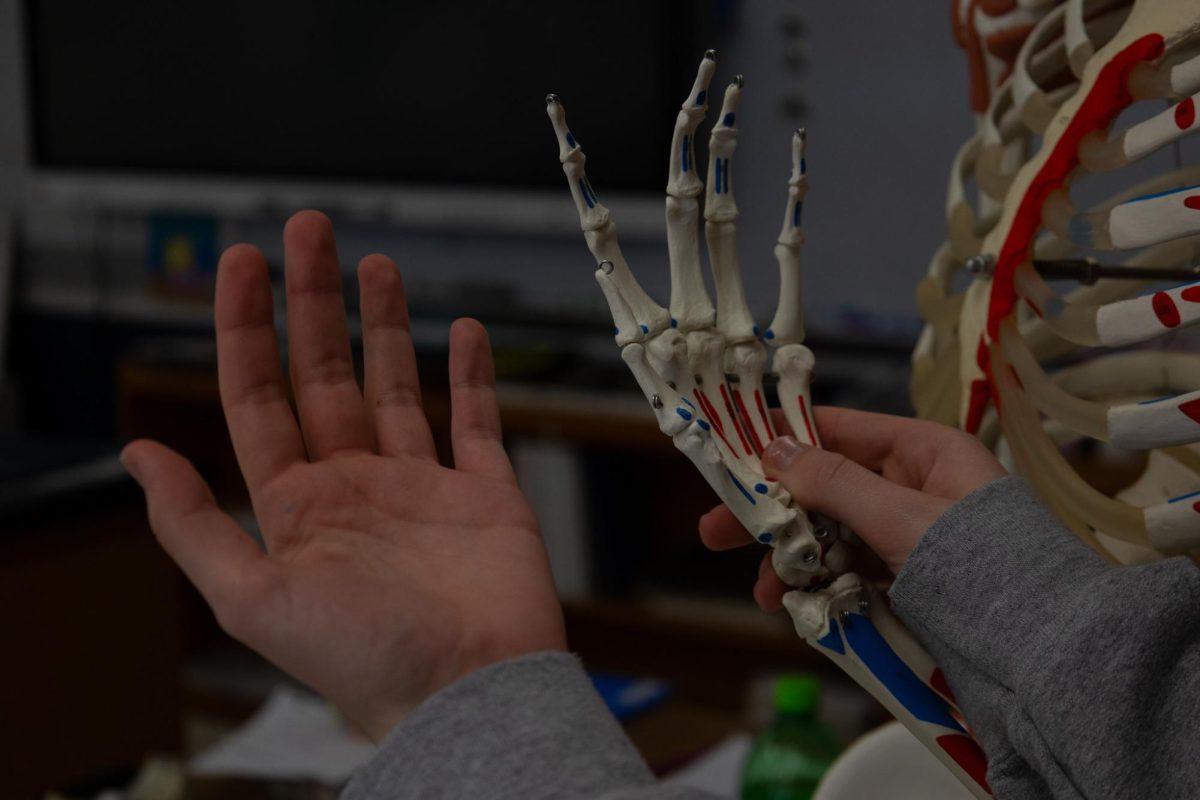

I saw members’ relief in finding out people were going through the same thing, but I also saw people’s relief when they found out a friend had survived a suicide attempt. I saw the start-up of pro-recovery group chats, but I saw invitations to chats centered around the encouragement of mental illness. I saw human skeletons, hospital beds, inspirational threads on how to starve yourself, and so, so many videos of people cutting themselves. Accounts pinned the weight they started trying to lose pounds at and their lightest, heaviest, and ultimate goal weights to the top of their profiles.

I admit, I would look at all of these to motivate myself to get worse. I didn’t think of it as “getting worse” until much later: rather, I would see it as an improvement. My body image had deteriorated to the point that I could barely look at myself any more, and my poor health made me fall asleep in most classes and made it harder to fight against my intrusive thoughts. I look back at it, and it makes me sad. Thankfully, not as much as being water-bloated used to make me.

But I saw people afraid at how much they had gotten themselves into, and I saw them talk about how they wished that they’d never chanced upon the space in the first place. Like me. I really wish that I’d listened.

Seeing people degrade themselves and others, openly asking for help on how to continue hurting themselves, and threads upon threads of glorified human skeletons helped me start to hate how I looked. So many people feel sad, out of control, too… but they also hate their bodies. I wouldn’t get that bad, right?

To this day, after numerous years of recovery from anorexia and other harmful behaviors, I sometimes still wish I had a stomach flatter than a board and miss what I looked like when I was an 87-pound freshman. I hate it—I hate feeling like this, and it makes me sad to think of what younger me went through.

I understand the want for community, and I understand that oftentimes it’s more of a need than a want. But there’s a boundary between enablement and support that this crosses: and the consequence can be deadly.