Censorship Disputes Diversity

Recent disputes against books have dually been challenging diversity in libraries

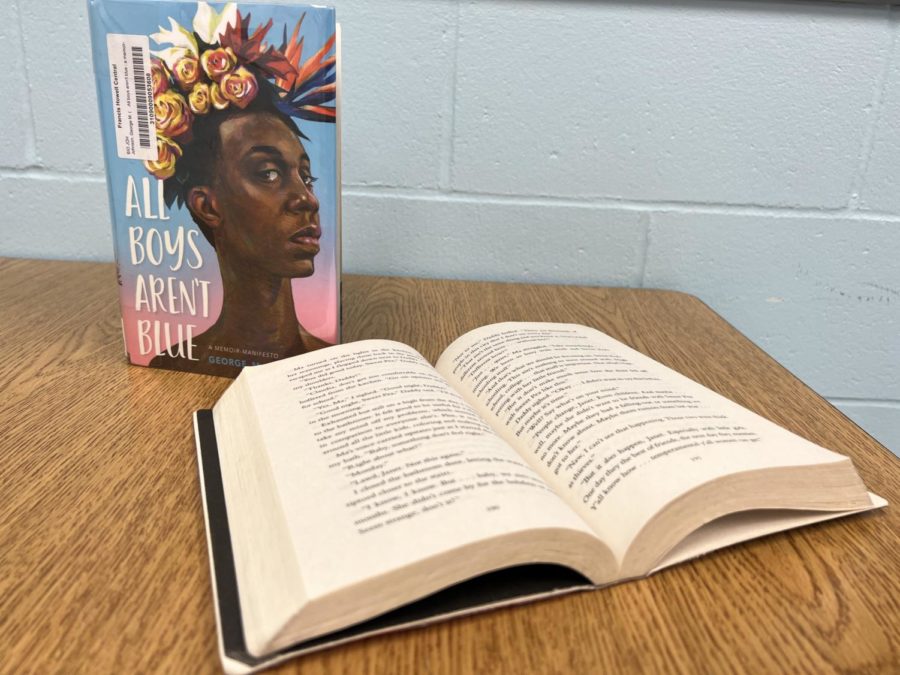

The contested novel “All Boys Aren’t Blue” rests against the wall while “Monday’s Not Coming” sits on the table open.

Senior Michaela Berry enters her English class to work on her project for the book “Monday’s Not Coming”. She analyzes the characters and truly becomes one with the book and its content, as it pertains to the lack of media coverage on the disappearances of African-American girls, like her. Little did she know, weeks later she would have to be part of a committee deciding if the book she had related to could stay in the district’s libraries.

Recently, in the district, there have been five challenges against books in the libraries of the school district. Many complaints were rooted in censoring sexual content and other inappropriate content such as drugs. The district has a procedure for reviewing books that have been challenged that include teachers, students, library media specialists, administrators, and parents. First, the department chair of English Mrs. Jessica Bulva is notified by Principal Dr. Sonny Arnel about the challenge.

“Dr. Arnel emails me with a notification that a book is being challenged and then asks me to find students and teachers who are willing to be on the committee to then analyze whether that book should be banned or stay in the library,” Mrs. Bulva said.

Although Mrs. Bulva has not been on a committee, English teacher Mrs. Christina Lentz has for the novel “All Boys Aren’t Blue” by George M. Johnson. According to Mrs. Lentz, the procedure is lengthy and structured.

“The committee members receive a timeline to read the book and a meeting date is set to discuss,” Lentz said. “At the meeting, all members introduced themselves and then had time to write their personal opinion on the pros and cons the book presents in terms of being in the school library.”

Even though there are many adult voices involved in this process, the district requires student input in order to allow students to have a choice and voice as well. Berry was the student element in the committee for the book “Monday’s Not Coming” by Tiffany D. Jackson. For Berry, being on this committee allowed her to call for representation for people of color in both the procedure and in the libraries.

“I got to put input on how people of color need to be represented and that we need to have that representation in literature,” Berry said.

The book Berry was asked to be on the committee was called “Monday’s Not Coming” by Tiffany D. Jackson, which features the problem about missing black girls not getting equal media coverage as a missing white girl would. Berry said these types of books can be hard to come by and are needed.

“I don’t see a lot of books that recognize Black people or something that has Black people overall,” Berry said. “You can have that ‘one Black friend’ in a book or a TV show, but it is more representation that matters.”

Diversity in the library is important to Berry, especially because as a person of color she looked up to this type of literature and is disheartened that people challenge these kinds of books.

“It feels like they are silencing black people, and I look up to this kind of literature because in school we have always been taught about what ‘the white man’ did,” Berry said. “It’s sad that these books are being challenged and pushed to be out of the library.”

Bulva agreed and goes on to mention that many students do not fit into the typical white cis-gendered straight archetype but they also need relatable characters who have experiences similar to them. So, keeping diverse texts can help meet the needs of the students who want representation.

“I have different students who say they feel like they don’t relate to the white main characters, so having these diverse texts allows them to feel like they are not alone in the issues they face,” Bulva said.

Library media specialist Tonisha LaMartina adds that it is important to both give students choice in the books they read and collaborate with parents to create boundaries that ensure appropriate books are on the shelves.

“We want parents to feel we are working with them, but also respect the student’s right to have some choice,” LaMartina said. “When you are working at a high school library the system is different, not every book can be on our shelves but can be at the public library because they are open to everybody,”

However, censoring books in the learning commons that make people uncomfortable can lead to larger problems. It can inhibit teenagers from understanding relevant topics they may come across as they grow up.

“It can be a slippery slope when we start to censor content that makes us uncomfortable,” LaMartina said. “For example, one of the challenged books, ‘Crank’, is about drug addiction which may be an uncomfortable subject, but is a reality and relevant for teenagers.”

LaMartina goes on to talk about how taking “Crank” and uncomfortable books like it off the shelves can prevent students from being able to understand these topics as they come across them. It can also keep them from being able to find content that relates to their lives or give them knowledge on something that can be prevented like drug addiction.

“It can be something they come across themselves, friends, or people they are close to, and to just take it off the shelves won’t help them relate or gain insight on the issues they are looking into,” LaMartina said.

These issues stretch farther than drug use and also include LGBTQ+ issues, racism, mental health, and sometimes involve sexual content. Although these parents challenge books that are of this nature, Mrs. LaMartina explains how even if these books are taken out of the shelves it will not remove the issues from society.

“Having the insight and the information can be powerful because if we take these books off the shelves the issues don’t go away,” LaMartina said. “It is still there, it is still relevant, and teenagers will still be conflicted with these situations.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Francis Howell Central High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs. FHCToday.com and our subsequent publications are dedicated to the students by the students. We hope you consider donating to allow us to continue our mission of a connected and well-informed student body.